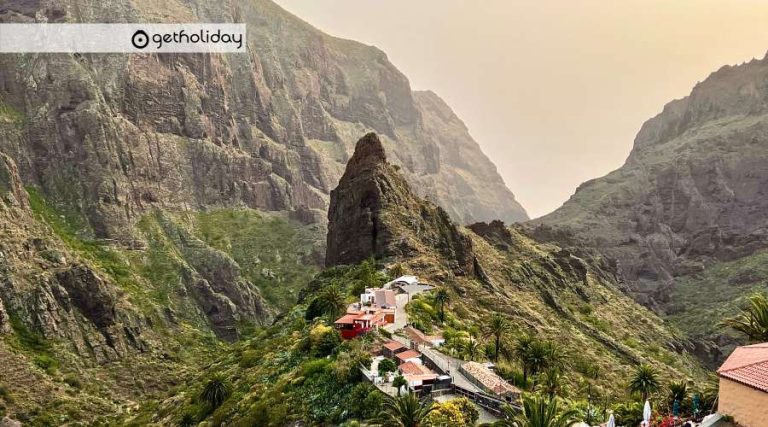

The Masca Canyon

In the next article, I will briefly introduce you to some of the reasons that make the Masca Canyon a unique place in the world.

The Masca ravine deserves its reputation.

The narrow canyon, carved tirelessly by the water on its way to the sea, is a magnet that attracts hundreds of visitors every day. The magnificence of the place should not distract you from finding the small treasures it holds. If you have the opportunity to visit it, keep all your senses open so that Masca allows you to discover its details.

Its legacy is formed by its geology, by the diversity of life that inhabits it, as well as by the traces left by the people who have been working in it for centuries.

But, despite its apparent hardness, the ravine is a fragile place. The interest it arouses to be visited should not jeopardize its conservation. For this reason, a management model has been established for its enjoyment, preservation of its values and the safety of the people who visit it. Complying with rules that appeal to your common sense, such as:

- take away all your waste,

- not to abandon the marked path,

- not to damage the flora or disturb the fauna by avoiding noise,

you will contribute to the conservation of this space.

Water allows us to look inside the earth.

It may seem incredible that something as “delicate” as water has been able to open this deep ravine. It is not unusual for water to excavate valleys, but in the case of Masca, it did so through resistant layers of hard basalt.

After the formation stage of the Teno massif, water has had 5 million years to sculpt the rock. Sometimes, calmly and slowly; sometimes impetuously. The climate in the Canary Islands has not always been similar to the present. For example, about 4 million years ago, frequent and torrential rains caused the ravine to have its most pronounced growth moment. Nowadays, when a good downpour falls, it is possible to see the changes in a short period of time. Materials fall from the walls and even the large stones of the riverbed are displaced. Every year the sculptor gives new touches to this masterpiece.

The cut that the water has made in the massif allows us to see the successive layers of materials that formed it. At the top, the most recent, the latest emissions of materials, and the lower down, the earlier and earlier in time.

Among these layers, there are some of a reddish color, called almagres, which are formed when a lava flow has been in the ground for so long that fertile soil has formed and has been colonized by life. With a new eruption that covers the previous layer, the previous soil, which becomes reddish and compact by a process called rubefaction. These layers then become impermeable, as when pottery is fired. For this reason, the almagres are very important, because they act as strata that prevent the rainwater from continuing to flow down into the earth, until it finds its way out in the form of springs or fountains.

On the walls of the ravine we can also see that the horizontal layers are cut perpendicularly by hundreds of vertical lines, like long mu- ros pointing skyward. These are the dikes. To form the upper layers, the magma had to break the already formed strata through huge cracks. At the end of each eruption, the cracks remained filled by the material that did not reach the surface, cooling very slowly and reaching great hardness. For this reason, erosion has a harder time dismantling them than the surrounding materials and they are highlighted in the relief.

In the deepest areas of the ravine, the water has carved so far down, that is, so far back in time, that we can see the first layers that formed the newly emerged island from the sea, more than 7 million years ago.

The Masca Gorge is an example of the diversity of life in Teno.

The itinerary of the ravine allows us to glimpse a part of the diversity of Teno. From the white broom (Retama rhodorhizoides) and palm trees (Phoenix canariensis) that grow among the houses and terraces of the Masca farmhouse, it then enters the ecosystem linked to the riverbed, before reaching the area closest to the sea, where the conditions for life are very different.

In Tenerife, there are not too many permanent water courses. Masca is one of the ravines that maintains a small stream during most of the year. This represents an oasis for life. Along the riverbed, species that cannot live without fresh water take refuge. The willows (Salix canariensis) are one of the few deciduous Canary Island trees and form an elongated forest, like a corridor along the stream. Sometimes their branches have a ghostly appearance, due to the webs of the caterpillars of an endemic moth, the spider moth (Yponomeuta gigas). In the puddles it is common to see dragonflies flying and many species of birds come to drink, such as the alpispa (Motacilla cinerea canariensis), always linked to watercourses.

However, life on vertical walls is much more challenging. The dragon trees (Dracaena draco) are perhaps the most showy plants, but other species such as the bejeques (Aeonium spp.) or the cliff cabbage (Crambe laevigata), are also tightrope walkers.

As we get closer to the coast, plants more adapted to the conditions of heat, low rainfall and salinity take over. The bitter tabaiba (Euphorbia lamarckii), the verode (Kleinia neriifolia) and the incense (Artemisia thuscula) are some examples. It is more difficult to locate the few specimens of species exclusive to the area, such as the Masca evergreen (Limonium perezii) or the Masca heartwort (Lotus mascaensis). The elusive Masca spider (Pholcus mascaensis) lives among these plants.

The cliff coast is the refuge of the spotted lizard (Gallotia intermedia), a species exclusive to Tenerife and one of our great treasures. Larger than the blight lizard, it has only managed to survive in small enclaves on the cliffs of Los Gigantes and Guaza. Also on this coast nest three or four pairs of osprey (Pandion haliaetus).

Both the Masca ravine and the cliff of Los Gigantes and the marine strip that bathes it are practically the last home for unique species. This is an added value to the spectacular nature of the tour, but also a responsibility not to worsen their situation and allow them to continue coexisting with our species.

The inhabited ravine.

Although today we visit it for its beauty, until a few decades ago the Masca ravine was visited assiduously for other reasons. The people who lived in the village had little time for leisure and contemplation, but they walked through it because it offered them a variety of resources.

Throughout the canyon there are traces of past uses, many of them related to the abundance of water. Areas cultivated with yams and fig trees. Drinking troughs to accumulate water and channels built in the walls of the canyon to carry this essential resource to other places…

The common reed (Arundo donax) is a species that was introduced in the Canary Islands to be used for various purposes due to the speed of its growth and the flexibility and resistance of its stems. It was planted in ravine beds and periodically cut. Today it is no longer used and has become a very aggressive exotic species. It needs to be controlled so that it does not occupy the space of willows and other endemic riverside plants. Another invasive species that has entered a few decades ago but has spread rapidly throughout the island is the cat’s tail (Pennisetum setaceum), which requires urgent measures to minimize its spread in the ravine.

Near the mouth of the river, there is a large hole that served as a shelter since time immemorial and on the beach, the new pier. This small infrastructure served to help the exchange of agricultural products from the Masca area for fish, wood and goods arriving from other villages.

Before there was a road, going down the 5 kilometers of ravine was not a bad option to move to other parts of the island. The itinerary that is followed today goes mostly on the route of an old traditional path with several centuries of accumulated footprints.

Today, the ravine is still inhabited, albeit temporarily, by hundreds of people who walk through it daily. To the spectacular nature of the route we must also add its invaluable natural and ethnographic heritage. The Masca ravine is a place that deserves our admiration, but also our commitment to its conservation.

Yours sincerely

Basso Lanzone guida de turismo de Canarias nr. 3900